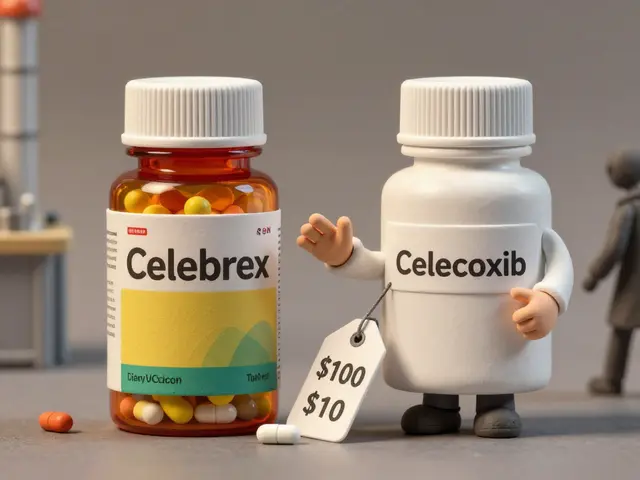

When a brand-name drug hits the market, it’s protected by patents that give the maker exclusive rights to sell it-often for 20 years. But here’s the catch: those patents don’t always line up with when the drug actually gets approved by the FDA. That’s where the 30-month stay comes in. It’s not a law passed yesterday. It’s been around since 1984, part of the Hatch-Waxman Act, and it’s still shaping who gets to sell cheap generic versions of drugs-and when.

What Exactly Is the 30-Month Stay?

The 30-month stay is a legal pause button. When a generic drug company files an application with the FDA to sell a cheaper version of a brand-name drug, they have to say whether they believe the patents on that drug are invalid or won’t be infringed. That’s called a Paragraph IV certification. If the brand-name company doesn’t like that claim, they can sue for patent infringement. Once they do, the FDA is legally blocked from giving final approval to the generic drug for up to 30 months. This isn’t a delay in review. The FDA still reads the application, checks the science, runs the tests. They can even give what’s called a “tentative approval”-meaning the generic is ready to go, legally and scientifically. But they can’t let it hit shelves until the 30 months are up, or the court rules in favor of the generic maker.Why Does This System Exist?

The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to strike a balance. On one side, you want generic drugs to come to market fast-cheaper meds mean lower costs for patients and insurers. On the other, you need to protect the companies that spent billions developing the original drug. Without patent protection, no one would invest in new medicines. The 30-month stay was designed to give brand companies enough time to resolve patent disputes without completely shutting down generic competition. It’s not supposed to be a permanent wall. It’s a clock. But in practice, that clock often runs longer than intended.How Long Does It Really Last?

The name says 30 months. But that’s not always the end of the story. If the lawsuit isn’t settled by then, the FDA can keep the stay going until the court makes a final decision. Courts can also shorten it if they find the lawsuit was filed just to delay competition. And here’s where things get messy. If the brand drug also has a five-year exclusivity period because it’s a new chemical entity, the total delay can stretch to nearly 40 months. That’s because the exclusivity period kicks in first, and the 30-month stay runs on top of it. Even after the stay ends, the generic doesn’t always launch right away. FDA data shows there’s usually a 3.2-year gap between when the stay expires and when the generic actually hits pharmacies. Why? Because the generic company might need time to ramp up production, negotiate with insurers, or deal with other legal hurdles.

Who’s Playing the Game?

The first generic company to file a successful Paragraph IV challenge gets a huge reward: 180 days of exclusive sales. No other generic can enter during that time. That’s why multiple companies often race to be first. In 2022, 72% of drugs facing generic challenges had more than one company filing a Paragraph IV notice. And drugs with multiple challengers got to market 8.2 months faster on average than those with just one. But this race isn’t cheap. A 2022 survey of generic manufacturers found that 63% spent between $3 million and $5 million per drug just on patent litigation. That’s money that doesn’t go toward making the drug-it goes toward lawyers, court filings, and expert witnesses. Brand companies aren’t sitting still either. They’ve learned to list more patents in the FDA’s Orange Book-the official list of protected drugs. In 1995, the average drug had 1.2 patents listed. By 2022, that number had jumped to 8.3. Many of these are secondary patents-on things like pill coatings, dosing schedules, or delivery methods-not the core invention. A 2019 Brookings study found that 67% of patents listed for top-selling drugs were filed after the original approval. These aren’t breakthroughs. They’re legal maneuvers.Is This System Working?

The numbers tell a split story. On one hand, since 1984, over 14,000 generic drugs have been approved. That’s saved U.S. consumers more than $2.2 trillion, according to former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb. Generic drugs now make up 90% of all prescriptions but only 23% of total drug spending. On the other hand, the FTC found that 78% of patent lawsuits involving generics ended in settlements that delayed generic entry beyond the patent’s expiration date. That’s called a “pay-for-delay” deal-where the brand company pays the generic maker to stay off the market. While courts have cracked down on these, they still happen. And the cost? The FTC estimates patent litigation delays add $13.9 billion to U.S. drug costs every year. That’s not just about the drug price. It’s about delayed access. A cancer patient waiting for a cheaper version of their treatment. A diabetic paying hundreds more because the generic hasn’t launched yet.

What’s Changing?

There’s growing pressure to fix the system. In 2023, Congress introduced the Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Act, which would cut the 30-month stay down to 18 months and ban stays for secondary patents. The FDA also proposed new rules to make patent listings in the Orange Book more transparent-forcing companies to prove each patent actually covers the drug. The biologics market is shifting too. Drugs like insulin and cancer treatments are increasingly biologics, which are made from living cells, not chemicals. They fall under a different law-the BPCIA-which gives them 12 years of exclusivity but doesn’t have a 30-month stay. So while small-molecule drugs are stuck in legal limbo, biologics are moving toward faster generic competition.What Does This Mean for Patients?

If you’re taking a brand-name drug and wondering when a cheaper version will arrive, the answer isn’t just “when the patent expires.” It’s “when the lawsuits end.” Even if the patent runs out in 2026, the generic might not hit shelves until 2028-or later-if the brand company files multiple lawsuits or settles with the first challenger. The system is designed to protect innovation. But too often, it’s being used to protect profits. The 30-month stay was never meant to be a tool for endless delay. Yet today, it’s one of the biggest reasons why patients wait years for affordable medicines.What’s Next?

The next five years will decide whether the 30-month stay stays as it is-or gets rewritten. With bipartisan support for reform and over $78 billion worth of brand drugs set to lose patent protection by 2028, the pressure is on. If the system changes, patients could see generic drugs arrive months, even years, sooner. Until then, the clock keeps ticking. And for many, every month counts.What triggers the 30-month stay?

The 30-month stay is triggered when a generic drug manufacturer files a Paragraph IV certification challenging a patent listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, and the brand-name drug company files a patent infringement lawsuit within 45 days of receiving notice of that challenge. Once the lawsuit is filed, the FDA is legally barred from granting final approval for up to 30 months.

Does the FDA stop reviewing the generic drug during the 30-month stay?

No. The FDA continues reviewing the generic application during the 30-month stay. In fact, they often issue a “tentative approval,” meaning the drug meets all scientific and regulatory standards. Final approval is just delayed until the stay ends or the court rules in favor of the generic maker.

Can the 30-month stay be extended beyond 30 months?

Yes. If the patent litigation isn’t resolved within 30 months, the FDA can extend the stay until the court reaches a final decision. Courts can also shorten the stay if they find the lawsuit was filed solely to delay generic entry.

Why do some generic drugs take years to launch after the 30-month stay ends?

The 30-month stay only removes the legal barrier to approval. After that, the generic company still needs to finalize manufacturing, negotiate with insurers and pharmacies, and sometimes deal with additional legal or regulatory issues. On average, there’s a 3.2-year gap between stay expiration and actual market launch.

How does the 180-day exclusivity period affect generic entry?

The first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell that generic version. This creates intense competition, with multiple companies racing to file first. Drugs with multiple challengers reach the market 8.2 months faster on average than those with only one filer.

Are there efforts to change the 30-month stay system?

Yes. In 2023, Congress proposed the Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Act, which would limit the stay to 18 months and block it for secondary patents. The FDA is also pushing for stricter rules on patent listings in the Orange Book. These changes aim to prevent abuse and speed up access to affordable drugs.

Rebecca M.

This system is a joke. People die waiting for cheap meds while Big Pharma counts cash. 😒

Lynn Steiner

They call it innovation but it's just legal extortion. I'm tired of seeing my insulin price stay the same while their CEOs buy private islands. 🇺🇸💔

dave nevogt

There's a deeper philosophical tension here - the tension between intellectual property as a social contract versus a corporate weapon. The Hatch-Waxman Act was born from a noble compromise: incentivize innovation while enabling access. But when secondary patents on pill coatings become litigation tools, we've lost the moral thread. The 30-month stay was never meant to be a multi-year delay tactic. It was meant to be a pause, not a prison. And now, with pay-for-delay settlements and patent thickets, we've turned a medical policy into a financial arms race. The real tragedy isn't that generics are slow - it's that we've normalized it. We accept waiting months or years for life-saving drugs as inevitable, when it's really just a failure of political will. We fund space telescopes but balk at fixing a system that kills people slowly, quietly, one uninsured prescription at a time.

Steve Enck

Statistically, the 30-month stay correlates with a 22% reduction in generic entry velocity, per JAMA 2021 analysis. The FTC's $13.9B annual cost estimate undercounts indirect societal burdens - lost productivity, increased ER visits due to non-adherence, and caregiver burnout. Moreover, the 180-day exclusivity window incentivizes strategic litigation rather than therapeutic innovation. The real problem isn't the duration - it's the opacity of patent listings. The Orange Book is a labyrinth designed for legal obfuscation, not public clarity. Until Congress mandates real-time, AI-audited patent disclosures with penalties for bad-faith filings, this system will continue to function as a regressive tax on the sick.

Ella van Rij

Oh look, another 12-page essay on how capitalism is bad. 🙄 Maybe if you spent less time crying about drug prices and more time learning how to budget, you wouldn't need generics. Also, typo: 'bipartisan' is spelled with two n's. Just sayin'.

Steve World Shopping

Patent thickets = rent-seeking behavior in pharmaceutical oligopoly. The 30-month stay is a regulatory capture artifact - a classic case of institutional sclerosis where IP law is weaponized to suppress competitive entry. The FDA’s tentative approval mechanism is functionally neutered by litigation risk, creating a de facto market monopoly extension. The 180-day exclusivity window creates perverse incentives for first-filer collusion. This is not market efficiency - this is legal arbitrage disguised as innovation protection.

Jack Dao

Wow. Just wow. You people act like drug companies are the villains, but who do you think funds the research? The same folks who complain about prices? 🤦♂️ You want cheap drugs? Then stop complaining about profit margins. Innovation doesn't happen on a nonprofit budget. And for the love of god, stop using emoticons like you're texting your grandma.

Paul Keller

Let’s not forget the human cost isn’t just financial - it’s emotional. I watched my mother wait 14 months for a generic version of her blood pressure med because the brand company sued over a patent on the tablet’s color coating. Fourteen months. She skipped doses. Her numbers went up. She didn’t complain. She just smiled and said, ‘It’s fine, honey.’ That’s not capitalism. That’s cruelty dressed up as law. The 30-month stay should be 18. And secondary patents? Ban them. Full stop. We’re not in 1995 anymore. We have AI, blockchain, transparency tools - we just need the will to use them.

Elizabeth Grace

i just want my diabetes meds to be cheaper and i dont care about all the legal jargon. can we just fix it already? 😭

Joel Deang

so like, the orange book is basically a cheat sheet for lawyers? lol. i had no idea so many patents were on stuff like 'this pill dissolves in 5 seconds' 🤡 also, who has time to read all this? i just want my pills to not cost my rent. 🤞

Roger Leiton

Just read this whole thing and I’m genuinely hopeful. The fact that Congress is even talking about capping the stay at 18 months and cracking down on secondary patents? That’s huge. And the biologics shift? That’s the future. We’re not going to fix this overnight, but if we keep pushing for transparency and limiting legal delays, we’re moving in the right direction. 💪💊