Swallowing feels simple-until it doesn’t. If you’ve ever felt food stick in your chest, or if liquids seem to take longer than they should to go down, you might be dealing with something more serious than occasional indigestion. Esophageal motility disorders are real, often misunderstood, and surprisingly common among people who experience persistent dysphagia. These aren’t just "bad digestion"-they’re problems with the muscles and nerves that move food from your throat to your stomach. When those muscles don’t contract properly, or when the lower valve won’t relax, food doesn’t move. And that’s when symptoms start.

What Exactly Is Happening in Your Esophagus?

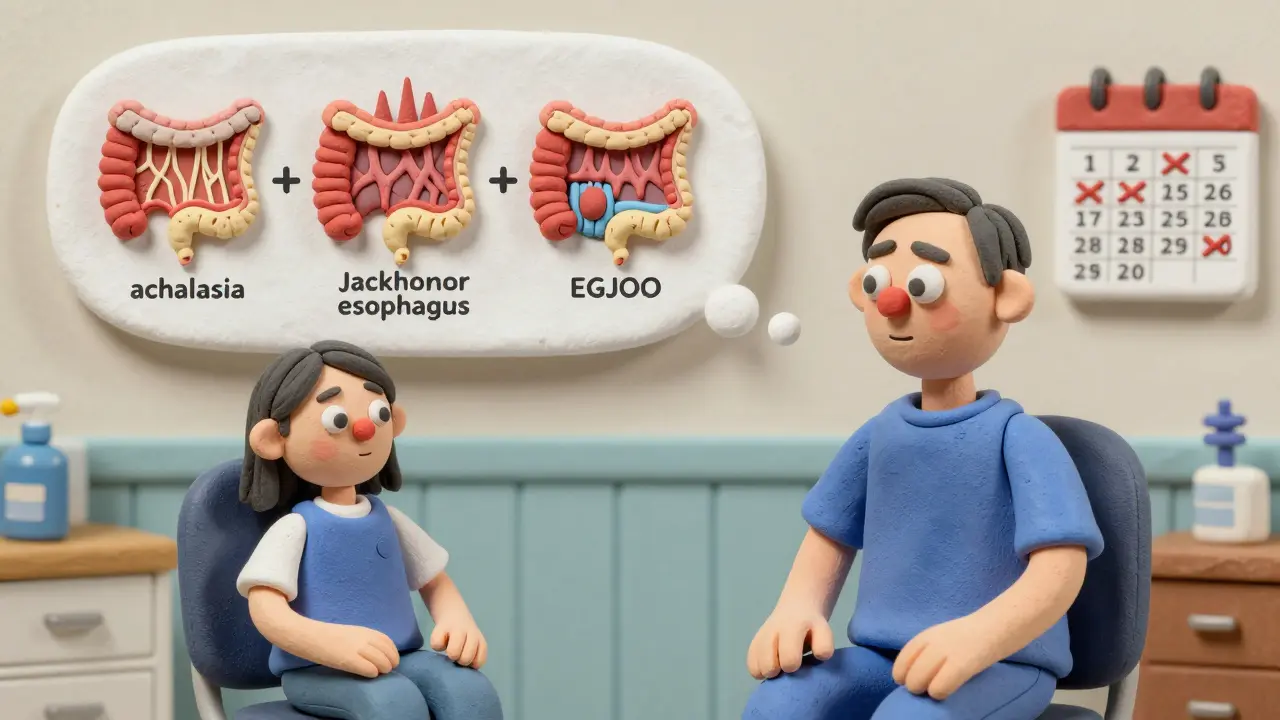

Your esophagus isn’t just a passive tube. It’s a muscular pipeline that uses coordinated waves of contraction-called peristalsis-to push food downward. Think of it like squeezing a toothpaste tube from the bottom up. In a healthy person, this happens smoothly, every time. In someone with an esophageal motility disorder, that wave breaks down. It might be too weak, too strong, uncoordinated, or the lower esophageal sphincter (LES)-the muscle at the bottom-might not open when it should. There are several named disorders, each with its own pattern. Achalasia is the most well-known. In this condition, the LES stays tightly closed, and the esophagus loses its ability to push food down. It’s like a gate that won’t unlock. Diffuse esophageal spasm causes wild, uncoordinated contractions-like your esophagus is having a seizure. Nutcracker and jackhammer esophagus are the opposite: the muscles squeeze too hard, sometimes with pressures over 180 mmHg, causing severe chest pain that mimics a heart attack. Then there’s esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO), where the LES is stiff but not completely closed, creating a partial blockage. These aren’t random quirks. They’re measurable. And that’s where manometry comes in.Why Manometry Is the Gold Standard for Diagnosis

You can’t see muscle contractions with an X-ray or an endoscope alone. That’s why doctors turn to esophageal manometry-specifically, high-resolution manometry (HRM). This isn’t your grandfather’s test. Modern HRM uses a thin, flexible tube with 36 tiny pressure sensors spaced just 1 centimeter apart. As you swallow water, the sensors record pressure changes along the entire length of your esophagus in real time. The result? A color-coded map that shows exactly where the problem is. The Chicago Classification system, updated in 2023, turned this data into a universal language for doctors. Before HRM and the Chicago system, two doctors might look at the same test and disagree on the diagnosis. Now, with standardized criteria, agreement jumps from moderate to excellent. That’s huge. It means fewer misdiagnoses. HRM doesn’t just diagnose achalasia-it classifies it. Type I (no contractions), Type II (pan-esophageal pressurization), and Type III (spastic contractions) each need different treatments. One size doesn’t fit all. And HRM doesn’t stop at pressure. It can measure how well the LES relaxes during multiple rapid swallows (MRS test), which tells doctors if the nerve signals are intact. This level of detail was impossible 20 years ago.Dysphagia Isn’t Always the Same

Not everyone with dysphagia has a motility disorder. But if you’ve had trouble swallowing for months-not just after eating spicy food or when you’re rushed-and if endoscopy shows no tumors, strictures, or inflammation, then motility testing is the next step. Many patients spend years being told they have GERD and are put on proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Those drugs reduce stomach acid, but they don’t fix a muscle that won’t relax. One patient from the UK described it this way: "I took PPIs for eight years. I still couldn’t eat bread. Then manometry showed jackhammer esophagus. Everything changed after that." The pattern of dysphagia matters too. In achalasia, it usually starts with solids, then progresses to liquids. In spastic disorders, it’s often triggered by hot or cold foods. Chest pain is common in nutcracker and jackhammer esophagus-up to 50% of patients end up in the ER thinking it’s a heart attack. And weight loss? It’s not rare. Around two-thirds of achalasia patients lose 15 to 20 pounds before diagnosis because eating becomes too painful or frustrating.

What Other Tests Are Used-and Why They’re Not Enough

Barium swallow used to be the go-to test. You drink chalky liquid, and X-rays track its movement. It’s good at showing if the esophagus is dilated or if there’s a "bird’s beak" narrowing at the bottom-classic signs of achalasia. But its sensitivity is only 78%. HRM catches 96% of cases. Barium swallow misses subtle patterns, like weak contractions or incomplete LES relaxation. It can’t tell you if the problem is Type I or Type III achalasia. That’s critical for treatment. Endoscopy is still the first test doctors order-but only to rule out cancer, strictures, or inflammation. It doesn’t measure muscle function. Impedance planimetry (EndoFLIP) measures how stretchy the esophagus is, which helps in complex cases like EGJOO. But it’s not widely available and doesn’t replace HRM. Wireless capsules like SmartPill can record motility over 24 hours without a tube, but they’re less precise and can’t measure LES pressure accurately. HRM remains the most complete picture.Treatment Isn’t One-Size-Fits-All

Once you know the diagnosis, treatment becomes targeted. For achalasia, there are three main options: surgery, endoscopic procedures, and dilation. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) cuts the LES muscle through small abdominal incisions. It’s been around for decades. Success rates? 85-90% at five years. But about 30% of patients develop reflux afterward. That’s why it’s usually paired with a partial fundoplication-a wrap that helps prevent acid from coming back up. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) is newer. A scope goes in through your mouth, and the surgeon cuts the muscle from the inside. It’s less invasive, has faster recovery, and similar success rates. But it comes with a higher risk of reflux-44% at two years compared to 29% with LHM. That’s a trade-off many patients accept. Pneumatic dilation uses a balloon to stretch the LES. It’s cheaper and doesn’t require surgery. Initial success is 70-80%, but nearly a third of patients need another dilation within five years. It’s often used in older patients or those who can’t have surgery. For spastic disorders like jackhammer esophagus, medications like calcium channel blockers or nitrates can help relax the muscle. Botox injections into the LES work temporarily-lasting 6 to 12 months. But for severe cases, POEM is becoming the go-to, even if it’s not officially approved for this use yet. Clinical trials are showing promising results.

The Real Challenges: Delayed Diagnosis and Access

The biggest problem isn’t treatment-it’s getting diagnosed. The average patient waits 2 to 5 years before seeing the right specialist. Nearly half consult three or more doctors before someone orders manometry. Why? Because doctors aren’t trained to think about motility disorders. Symptoms get blamed on stress, GERD, or anxiety. And HRM machines cost $50,000 to $75,000. They’re not in every hospital. In the UK, they’re mostly in academic centers. In rural areas or low-income countries, access is nearly nonexistent. Training is another hurdle. Interpreting HRM takes months of practice. After the Chicago Classification was introduced, inter-observer agreement jumped from 65% to 88%-but only after physicians completed formal training. Without it, even the best data can be misread.What’s Next? AI and Better Tools

The field is moving fast. AI tools are being trained to read manometry tracings. Early studies show they can identify achalasia with 92% accuracy-better than untrained human interpreters. That could make diagnosis faster and more consistent, especially in places with few specialists. Wireless capsules are improving. New versions may soon measure both pressure and pH, giving a fuller picture. Magnetic sphincter augmentation (LINX device) is being tested for select achalasia patients with some remaining peristalsis. Early results show 75% symptom improvement at one year. But the biggest breakthrough might be awareness. More gastroenterology fellowships now require motility training. Medical schools are starting to teach it. Patient advocacy groups are pushing for earlier testing. And with the Chicago Classification v4.0 now standard, doctors worldwide are speaking the same language.What Should You Do If You Have Dysphagia?

If you’ve had trouble swallowing for more than a few weeks:- See a gastroenterologist-not just your GP.

- Ask if an endoscopy has been done to rule out physical blockages.

- If endoscopy is normal, ask about high-resolution manometry.

- Don’t assume it’s GERD. PPIs won’t fix a muscle problem.

- Bring your symptom history: when it started, what foods trigger it, if you’ve lost weight, if you have chest pain.

Is dysphagia always caused by esophageal motility disorders?

No. Dysphagia can be caused by structural problems like tumors, strictures, or esophagitis from acid reflux. It can also be neurological, such as after a stroke. That’s why doctors start with an endoscopy to rule out these causes before moving to motility testing. Only after structural issues are excluded should manometry be considered.

How painful is high-resolution manometry?

Most patients report mild discomfort, like a sore throat or pressure in the back of the nose. About 35% say it’s uncomfortable enough to make them want to stop, but it rarely causes pain. The tube is thin and lubricated. Local anesthetic spray helps. The test lasts about 20 minutes. Many patients say the discomfort is worth it once they get answers.

Can I have manometry if I have a pacemaker or other implants?

Yes. High-resolution manometry uses no electricity or radiation. It measures pressure only, so it’s safe for people with pacemakers, defibrillators, or other implants. There are no known contraindications for the procedure itself.

Are esophageal motility disorders hereditary?

Most are not inherited. Achalasia, for example, is considered an autoimmune condition in many cases, possibly triggered by a viral infection. There’s no clear genetic link. However, some rare syndromes like Allgrove syndrome or Down syndrome are associated with higher rates of achalasia. For most people, it’s not something passed down in families.

Can lifestyle changes help with esophageal motility disorders?

Lifestyle changes alone won’t fix the muscle dysfunction, but they can help manage symptoms. Eating slowly, chewing thoroughly, drinking water with meals, and avoiding very hot or cold foods can reduce discomfort. Sleeping with your head elevated helps prevent regurgitation at night. For some, eating smaller, more frequent meals makes a noticeable difference. But these are supportive-not curative.

What happens if I don’t treat my motility disorder?

Left untreated, chronic dysphagia can lead to malnutrition, weight loss, and aspiration pneumonia if food enters the lungs. In achalasia, the esophagus can become massively dilated and lose its muscle tone over time, making treatment harder. In spastic disorders, ongoing intense contractions can cause chronic chest pain and reduce quality of life significantly. Early diagnosis and treatment prevent these complications.

Esophageal motility disorders are complex, but they’re not mysterious anymore. With modern tools and better classification, doctors can now see what’s wrong-and fix it. If you’ve been struggling to swallow, don’t wait. Ask for the right test. Your next meal shouldn’t feel like a battle.